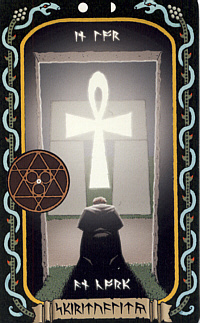

The Tale of Shamino and the Spirits

“The Tale of Shamino and the Spirits: a Parable of Spirituality” was originally featured on the website for Ultima IX, but is no longer available except from Prima's Official Guide to Ultima IX: Ascension:

The dead of Britannia have always been a restless lot. Why this should be I do not know, but I have sometimes thought that the vitality of the land itself is so great, it bestirs the memory of itself even in lifeless flesh.

Be that as it may, my final tale concerns itself with a certain town, where the inhabitants of the graveyard had forgotten their proper decorum. Nor was this a mere aimless revenant or two, but a veritable plague of lifeless stalkers. Most every night was disturbed by a squad or company of the dead making riot, for the creatures did not wander aimlessly, but set themselves about the business of terror and destruction with a methodical efficiency that demanded a malign will behind their excursions.

It was obvious to the villagers that this was not a problem to be dealt with by a few torches and pitchforks, or a cantrip or two. So they sent to Britain to pray the King for aid.

Their call was answered most expeditiously, for Lord British bade none other than Shamino the Ranger, first hero of Britannia and best and oldest friend to His Majesty, to deal with the situation.

Shamino soon arrived, and set immediately about his work with sword, bow and shield. The ranks of the shambling revenants he quickly reduced to a few small piles of putrescent but inanimate flesh. With his way thus cleared, he was able to enter the graveyard itself, where he discovered a newly opened tunnel, which lead to an ancient catacomb far below.

In that dank and haunted place, Shamino found the source of the trouble, a lich, an ancient and potent spirit from the First Age of Darkness. For centuries the evil thing had lain dormant in its stygian tomb, but of late it had bestirred itself, and in its ancient malice had begun the current harassment of the living above.

So Shamino found the thing, and there he slew it, in a night-long battle of blade and spell. And if you think I pass over such an epic battle with undue haste, know that it is merely the prelude to my tale proper.

With the evil wight dead, Shamino elected to remain in the town for a while, to recover from his battle, and to insure that the restless evil was indeed put down.

It was well he did, for scarce two nights after the lich’s most recent and final death, a lad of the village was brought before Shamino in a pitiable state of terror and nervous exhaustion.

When the lad had calmed enough to speak at last, he told how he had gone to pass an hour in the graveyard on a dare, thinking the evil all departed. But he had scarce arrived when he was set upon, not by crawling corpses, but by a howling cloud of spirits. He could not understand their gibberings, but so great was the force of the despair and desperation in their voices that he vouchsafed he would have far preferred to face an honest undead body.

Shamino was not overly surprised to discover that the lich’s malice had stirred up forces that its destruction had failed to quell, so he spent the day in preparation, and that night took himself again to the graveyard, an hour or so before midnight.

He was through the gate scarcely a minute when he was set upon by the cloud of ghosts, and the sorrow of their incoherent wails and moans tore at his very soul. He sensed no evil in the things, but only a terrible, lonely despair that raked his soul and mind.

But Shamino was made of sterner stuff than the village lad, and he shut the howls out of his mind (for the things had no power to touch him physically), and made certain preparations. At last through arts that he knew, the spirits were quieted (albeit temporarily), and held in that place before Shamino.

Then Shamino indicated the first of the spirits, and bade it, “You there, speak now, and tell me plainly why you haunt the night.”

“In my life,” the spirit sighed, “I was rich, and gloried in my riches, but did nothing to use them to help those around me, and now I see my life meant nothing.”

“Your pride was great,” said Shamino, “but where is it now? Look about you, you rest in a grave no finer than many of the poor folk you ignored. Rest now, and take comfort in the Humility of death.”

And the spirit heard Shamino’s words and, acknowledging them, vanished away. (Now it may seem odd that a restless spirit would be banished at a mere word, but Shamino the Ranger was no common man, and when he spoke on matters of Spirituality, he spoke with Authority, so that creatures of the supernatural planes might be compelled by his very words.)

Then the next spirit spoke, and it said, “In my life I put on airs, telling folk that I was a hero, or a noble, or possessed skills that were not mine, hoping thereby to find friendship and fortune. And I see now that everything I gained falsely was itself false.”

“And yet,” replied Shamino, “you still take on the seeming of that which you are not, for you pass among the living and trouble their lives. Put dishonesty behind you and be what you are. Rest now in the Honesty of death.”

“In my life,” said the third spirit in its turn, “I thought that I was a wolf among men, and the weak were my prey. I took the little that they had, and thereby accrued much for myself. But now I mourn, for I was most bitterly hated.”

“Why then do you still trouble the living?” asked Shamino. You regret your lack of Compassion in life, but I tell you to rest, and thereby learn Compassion from death, which ends all pain and sorrow, even thine.”

“In my life,” the fourth spirit began, “I ran from danger, while those I cared for stood and fell. Now I see how much finer it would have been to have died in the glory and comfort of their companionship, than to have gone on to the guilty and futile life which I led.”

“And you are still running,” said Shamino, not without kindness. “Let rest your fear, and Valiantly embrace the mystery of death. Your friends and loved ones await you.”

The fifth spirit took up the litany, saying, “In my life, I stood up in defense of the guilty, to gain by their friendship, and spoke out against the innocent when so bidden by my masters. Can there be any payment now for the wrong I did?”

“You seek restitution for your deeds, but you flee the judge which all men must face. If you hunger for Justice, you will find the Justice of death, which is the proper sentence of all in the end.”

“I was a miser in life,” said the sixth, “And I sat alone with my wealth all my days. I did nothing of importance to anyone, not even providing honest work to those whom I might have hired, for I valued my gold above their service. Where is my gold now?”

“Gold indeed is forever beyond your reach, but there remains one Sacrifice within your power to make, and that is to Sacrifice this sad unlife to death, which patiently awaits your gift.”

Now only two spirits remained, swirling sadly in the moonlight, and at last one was moved to speak.

“In my life, I served a man who loved me, and valued my service and friendship above all else. I betrayed him, seeking greater wealth and power. Now I see that I gained nothing and lost all, for those I came to serve saw me as only the worm which I was.”

“The evil you did was very great,” Shamino said gravely, “And I cannot offer you absolution. But see now that one final obligation awaits you, which you have yet to fulfill. Will you not Honorably go through the final veil of death?”

Then only final ghost drifted on the breeze, and seemed little inclined to speech, until at last Shamino broke the silence.

“Speak, o spirit, and tell me of the sin which torments you in your unnatural waking.”

“I have not sinned,” the ghost replied, “for I honor the Virtues to the best of my ability.”

“Be that as it may, why then do you thus linger after your death?” Shamino inquired.

“I am no dead ghost,” the thing replied, “but have been cast out of my own body by the evil thing that formerly haunted this place. Pray reunite me with my body, that I may resume my rightful span of corporeal years.”

Now such things are not unknown, but to the keen sight of Shamino, the difference between a living spirit and an unliving shade is as clear as the difference between a strong young oak and an ancient rotting stump.

“You are mistaken, friend,” Shamino said with all gentleness. “You are truly dead, my word and oath on that. You must now go to your final rest, and cease to trouble the living.”

“You lie,” howled the spirit, “For I move and see and speak. How then can I be dead? I live! I live!” Then it tried to break free of Shamino’s binding and assail him, but the wards were well-wrought, and the dismissal of the other spirits had far weakened the ghost’s unnatural energies.

Then Shamino knew what kept the spirit bound to earth, for it is the nature of the Spiritual to see the reality of things that are hidden from the less gifted. This creature was most damnably cursed, for its curse was of its own making. Where the other ghosts had been tormented by the knowledge of their sin, this one tortured itself by withholding knowledge. The ghost lied to itself, cowardly running from death, hating itself and its true nature. In this, it rejected all three of the great Principles, which together compose the ultimate Virtue of Spirituality.

Shamino stood for awhile, regarding the pathetic thing, and at last he spoke. “I can do nothing for you. Go about your existence, if such it can be called.” And he dispelled his wards and left that place forever.

As for the ghost, it haunted the graveyard thereafter. It no longer had the power to terrorize the living, but only lurked about, moaning and sighing to itself in the darkness of the night, and of its own delusion.

– from Ultima IX

See Also[edit]

| Parables of Virtue | |

|---|---|

| The Tales | “Prologue” ☥ “Katrina and the Noble” ☥ “Mariah and the Demon” ☥ “Iolo and the Brigand” “Geoffrey and the Dragon” ☥ “Jaana and the Goblin” ☥ “Julia and the Clock” “Dupre and the Gargoyles” ☥ “Shamino and the Spirits” ☥ “Epilogue” |