The Tale of Julia and the Clock

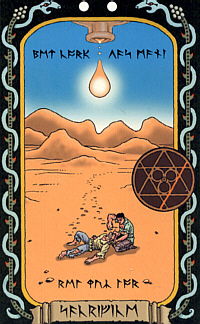

“The Tale of Julia and the Clock: a Parable of Sacrifice” was originally featured on the website for Ultima IX, but is no longer available except from Prima's Official Guide to Ultima IX: Ascension:

In olden days Minoc was well known as the center of all the finest artisans and craftsmen of the land, and among that honored company two were most famous. Jervaise, the carver, was everywhere acclaimed one of the greatest artists Britannia had ever produced, being able to create items from rock or wood that were not only durable and practical, but also astounding works of fine art. A table or lamp from the hand of Jervaise was valued above many a marble statue or painted portrait in the great houses of the land. The other, younger, dean of Minoc’s crafters was Julia, the Tinker. While Jervaise was, above all, an artist, Julia was an artisan. It was said her timepieces would remain accurate to the very second for a hundred years, if kept wound and properly tended. She also invented many cunning devices of the sort to make difficult tasks both simpler and more precise.

When one of the great nobles of the land wished something that was both beautiful and intricate, he would often commission both Julia and Jervaise to work together on it, and these collaborations became almost instantly the stuff of legends.

As for Jervaise and Julia themselves, they were content in their work, and they charged their patrons a rate worthy of their skills, so that they became two of the most prosperous citizens of Minoc, in addition to being two of the most celebrated.

So it came to pass that one day a messenger came from a rich noble of the city of Moonglow, a place where cunning objects of extravagant beauty were greatly prized. This noble desired (the messenger said) a great clock to be made, of unsurpassed beauty and complexity. It was to be constructed out of the finest wood and marbles, and to be capable of showing not only the time, but also the phases of the moons and the progress of the Zodiac, the season and the year, and to predict the weather for the day. All this was to be told through the actions of a troupe of various cunning and amusing automata, and accompanied by lovely music. The terms for this commission were to be a rich sum immediately, for material and expenses, generous annual payments for the duration of the task, and the proverbial small fortune upon completion.

Julia and Jervaise took council together, and returned a reply that the thing could be completed in six years of work. The messenger received this news and delivered the first payment, without further haggling.

The two, having no other major commissions just then, immediately threw themselves into the work, drawing up the intricate plans and sketches, and sending them to their patron in Moonglow, where they were rapturously received. At that, Jervaise ordered the rich materials for the case and fittings of the clock, while Julia began work on the core of the mechanism.

Two years later the clock was taking shape nicely, and Julia privately thought that they might even deliver it early to their patron. Then one day the messenger from Moonglow returned, bearing a single curt letter. It said that their patron had died of a fever, and his estate had gone to his sister. Which lady, not sharing her brother’s taste for finery, had no desire to continue to pay to see the clock finished. There would be no further payment, the letter said, but the artisans could keep the rich materials for the unfinished clock as compensation for the breaking of the contract.

At this news Julia swore in a most unladylike fashion, and for a very long time, but in the end she had to admit that they’d had a good two years’ income off the thing, though what a pity it would never be finished. Then she went off to draft new replies to other potential commissions that she had been planning to refer to others. As for Jervaise, he just sighed, and sat looking at the unfinished clock until far into the night.

A few days later Jervaise asked Julia if she minded if he looked for a new buyer for the clock, rather than selling it for the raw materials. She agreed, by this time rather wishing never to see the thing again.

For the next year and more she heard little from Jervaise. He politely refused all joint commissions, saying he was otherwise occupied. When Julia inquired if he had any new buyers for the clock, he only shook his head, with a sad smile.

Then, one day Julia was out near the mines on the outskirts of town on an errand, and there she saw Jervaise, pulling a handcart of ore in the hot summer sun. Now the mines of Minoc were always hiring laborers, but this was the lowest and least paid of all tasks in that city. Jervaise was stripped to the waist against the heat, and Julia could see that his weathered old skin was stretched painfully tight against his prominent ribs. As she watched in horror, scarcely believing her eyes, she saw the cart slip from her friend’s frail grasp, as he crumpled to the ground in a faint of hunger and exhaustion. The foreman began to bellow and shake the fallen craftsman, calling him lazy and worthless, but Julia rounded on the lout with curses and wrath, and he fell back. In the end she paid a pair of mine workers to pick up Jervaise and bear him back to town, where she brought him to her house.

For several days he lay there raving, while Julia fed him broth and watered wine, but at last he regained consciousness. He then confessed that after the loss of the commission, he could not bring himself to stop work on the clock, which he regarded as his masterpiece. There were no new buyers, for nobody wished to spend so much on such an extravagant thing. Yet Jervaise had refused all other commissions, only taking occasional odd jobs when he needed money to buy food. But this last time he could not bring himself to quit the clock until he was so weak with deprivation that he could not complete the work he needed.

Julia was astonished at this, and she spent long hours trying to reason or bully the old man into abandoning the clock and resuming his former practice. Jervaise listened in patience, but at last he only shook his head and said, “Don’t you see, girl … money is nothing, but the clock is all.”

So at last Julia gave up in disgust, but thereafter she saw that meals from her own table were taken to Jervaise every day. Thus freed from the threat of starvation, Jervaise began a sort of impoverished but busy retirement, he who was once one step away from being the richest man in Minoc. Every day he worked on his clock, but the work went slowly, for he had no money for assistants to hasten the task.

About two years later, Jervaise did not answer when Julia’s servant knocked with his supper, and when the maid entered the workshop she found Jervaise lying dead at the foot of the clock, his smallest hammer and chisel in his hand, and a small, strange smile on his face.

They found a will, which left everything to Julia, but by that time “everything” consisted of Jervaise’s ancient workshop, his tools, and his still-unfinished clock.

On the day they buried him, Julia went to the workshop alone. There she ran her hands over the intricate carving of the case, spotting with her practiced eye the few areas still awaiting attention. She fondled the tiny and colorful figures Jervaise had created, and thought for the first time in years about the subtle machinery with which she had once planned to give them life.

As she left the workshop, she was accosted by a messenger from Britain, who told her that Lord British himself requested that she create for him a new kind of telescope. “Tell his majesty thank you,” she replied, “but I have a previous commission that I must complete first. If Lord British should wish to renew his offer in, say, three years’ time, I would be most interested.”

For the next three years Julia was little seen in Minoc. She did not receive visitors, and she dismissed all her servants and apprentices except for an old neighbor woman who swept her house and cooked her evening meal. Her own workshop stood empty, for she was working in the one which had formerly belonged to Jervaise.

And then, after three years, she put a heavy lock onto door to Jervaise’s workshop, and rehired her staff, and let it be known that she was once again receiving commissions. She was soon busier than ever, for her reputation had not been dimmed by her sabbatical, and she even built the king’s telescope, which job had been kept open awaiting her convenience. And in later years she would sometimes go all alone into Jervaise’s workshop, and stay there for several hours, and passersby could hear faint and sweet music coming out of the old building. But those few who actually saw the inside said it was totally bare, save for a tall box or cabinet in one corner, covered with a heavy cloth.

– from Ultima IX

See Also[edit]

| Parables of Virtue | |

|---|---|

| The Tales | “Prologue” ☥ “Katrina and the Noble” ☥ “Mariah and the Demon” ☥ “Iolo and the Brigand” “Geoffrey and the Dragon” ☥ “Jaana and the Goblin” ☥ “Julia and the Clock” “Dupre and the Gargoyles” ☥ “Shamino and the Spirits” ☥ “Epilogue” |